|

by _56_Ghost_61 |

|||

|

|||

|

|

|

|

A special note needs to go out to _56_Doglips_61 for without his leadership and devotion to the squadron we would not have made it to where we are today. Thanks Doglips! |

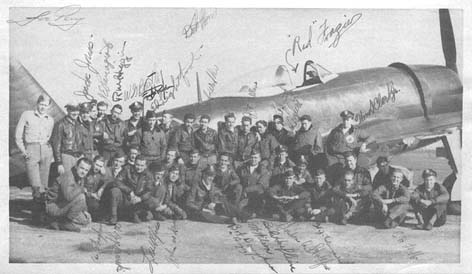

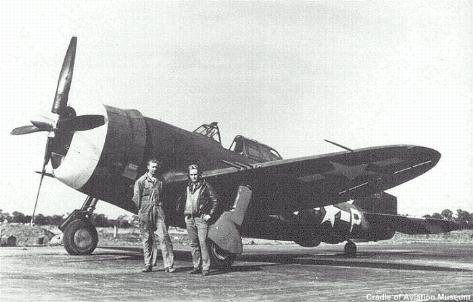

The Pilots of the 56th in front of one of the 61st Squadrons p-47's

The 56th Fighter Group was born in Savannah, Georgia in January, 1941, as the 56th Pursuit Group. Its earliest history was marked by frequent moves; the first to North Carolina in May 1941 and then to New York in 1942. Using P-39 and P-40 aircraft, the unit flew air defense patrols until June 1942, when the unit became the first to train with and fly the P-47 Thunderbolt.

The Group left for England on January 6, 1943, and comprised the 61st 62nd

and 63rd Fighter Squadrons, and was renamed the 56th Fighter Group. During the

following two years, pilots of the 56th destroyed more enemy planes and listed

more aces than any other Army Air Force group in the 8th Air Force, including

the top two aces in Europe. By the war's end, the wings motto - "Cave

Tonitrum," "Beware the Thunderbolt" - was highly respected by

both the allies and its enemies. It was also during this period the Group earned

the title "Zemke's Wolfpack" derived from Col. Hubert "Hub"

Zemke, the Commanding Officer of the 56th Fighter Group. He knew the strengths

and weaknesses of the P-47 and, rather than switch to the new P-51 Mustangs, he

decided to retain their Thunderbolts. The 56th was the only 8th Air Force group

to fly the P-47 until war's end. The P-47 Thunderbolt was the perfect weapon for

the job. It was ruggedly built and had eight hard hitting .50 caliber machine

guns. It was also a good dogfighter when it's best attributes were exploited.

Through Hub's superb leadership, his faith in his men and his aircraft,and the

skill and determination of the pilots, the 56th Fighter Group earned a permanent

"place at the table", as well as a place in history.

The Germans who fought against the Wolfpack were proud to have had the honor.

On

October 18, 1945 the unit was inactivated. It was reactivated May 1, 1946 at

Selfridge Field, Michigan., as part of the Strategic Air Command's 15th Air

Force. It still was made up of the 61st, 62nd and 63rd Fighter Squadrons. In

July and August 1948, a major operation of the wing involved 16 of it's F-80's.

The flight proceeded to Furstenfeldbruck, Germany, by way of Maine, Labrador,

Greenland, Iceland and Scotland. Although the operation was not connected with

the Berlin Airlift, it did focus world attention on the U.S. Air Force's ability

to rapidly deploy jet fighters during a crisis.

The Group was transferred from Strategic Air Command to the Continental Air

Command's 10th Air ForceDecember 1, 1948 and the mission of the tactical units

was shifted to air defense. The unit was redesignated as the 56th Fighter

Interceptor Wing on January 20, 1950. Its 61st, 62nd and 63rd Fighter

Interceptor Squadrons converted from the F-80 Shooting Star to the F-86 Sabrejet

in April 1950.

The wing, with the exception of the four tactical squadrons, was deactivated

February 6, 1952. The tactical squadrons were reassigned to the new air defense

wings as part of a general reorganization of the Air Defense Command. Almost

nine years later, having been redesignated the 56th Fighter Wing (Air Defense),

the wing was reactivated at K.I. Sawyer AFB, Michigan., again with an air

defense mission. The wing controlled a single tactical unit, the 62 FIS, flying

the F-101 Voodoo.

From February 1, 1961 to October 1, 1963, the wing was part of the Sault

Sainte Marie Air Defense Sector. From October 1, 1963 to January 1, 1964, the

wing was an important part of the Duluth Air Defense Sector. Under both sectors,

the wing participated in many ADC exercises, tactical evaluations and other air

defense operations. The single tactical squadron was placed directly under

Duluth Air Defense Sector December 16, 1963, leaving the wing without a tactical

mission. On January 1, 1964, the wing was assigned to SAC and inactivated.

Slightly more than three years later, the wing was once again activated, this

time at Nakon Phanon Royal Thai AFB, Thailand. The unit was designated the 56th

Air Commando Wing and had a complex combat mission in the war then raging in

Southeast Asia. Assigned to 13th Air Force, the wing received operational

direction from 7th Air Force in Saigon. The combat and support operations of the

wing in Southeast Asia were numerous and varied. Until August 1, 1968, the wing

operated as an air commando organization. Special missions were the rule rather

than the exception during the entire period of the wing's stay in Thailand. It

strongly supported the Southeast Asia conflict in a wide variety of specialized,

as well as general operations, directly carrying the flight to the enemy. The

wing and its units participated in every military campaign beginning with the

Vietnam Air Offensive, Phase II. The wing headquarters earned unit Awards with

the Combat "V" device and the Republic of Vietnam Gallantry cross with

Palm. Individual units of the wing shared in some of these awards as well as

earning others on their own.

On June 30, 1975, the 56th U.S. Air Force Hospital and 56th Consolidated

Aircraft Maintenance Squadron, two of the wing's subordinate units, were

activated. The wing itself, together with its supply and transportation

squadrons and its combat support group (the latter containing its security

police and civil engineering squadrons) moved without personnel or equipment to

MacDill AFB. The wing was redesignated the 56th Tactical Fighter Wing and

assigned to Tactical Air Command's 9th Air Force. The 1 TFW and several newly

activated units bearing the "56th" designation also replaced similar

units bearing the "1st" designation. The inactive 61 and 62 FIS were

redesignated as tactical fighter squadrons and the 63rd Fighter Interceptor

Training Squadron was moved without personnel or equipment from Tyndall AFB,

Florida redesignated as a tactical fighter squadron and assigned to the 56 TFW.

Finally, the 4501st Tactical Fighter Replacement Squadron, later redesignated

the 13th Tactical Fighter Training Squadron, and the U.S. Air Force Regional

Hospital, MacDill, were reassigned from the 1 to the 56 TFW.

On October 1, 1981, the wing had its designation changed once again. The wing

changed from a tactical fighter wing a to tactical training wing. This

designation was brought about because of the conversion from the F-4D Phantom II

to the F-16 Fighting Falcon. The transition process began in November 1979, and

was completed in June 1982. With the change in the wing's title, each of its

squadrons have also had name changes. The 61st, 62nd and 63rd became tactical

fighter training squadrons and the 13th was deactivated July 1, 1982. The 72

TFTS was activated on the same day and was one of the four squadrons of the 56th

Tactical Training Wing.

June 27, 1988, marked another transition for the wing. It began its

conversion from the F-16A/B models to the updated F-16C/Ds. With the F-16C/Ds,

the wing remains the primary F-16 aircrew and maintenance training wing in the

Air Force. The wing was reassigned to Luke AFB April 1, 1994. Under the 56th

Fighter Wing, which retains its F-16C/D training mission, is the 21st, 61st,

62nd, 63rd, 308th, 309th, 310th and the 425th Fighter Squadrons.

We the Members of the Virtual 56th Fighter Group of Fighter Ace 2 of the Zone can only hope to emulate the Honor, Gallantry and Skill of these Brave Men of the Original 56th Fighter Group. We all wish to take this moment to thank them and their families for the extreme hardships they endured so that we today can enjoy what we have. For those who paid the ultimate price in WWII we offer our thoughts and prayers and our eternal gratitude. LEST WE FORGET!

As stated in the History of the 56th, this was the most successful Army Air Force Fighter Group in the 8th Air Force.

The 56th was part of the 8th US Army Air Corps. Before we begin let me take a minute to tell you what a fighter group actually is. A fighter group was three fighter squadrons plus additional maintenance and headquarters functions and was commanded by a Colonel. In the 8th Air force squadrons did not operate independently. All three squadrons were based at the same airfield and operated within the group. A fighter squadron was a unit staffed to operate independently and usually contained about 250 personnel. There were about 27 flying officers, a half dozen ground officers, and 25 aircraft. Usually the Commanding Officer CO), always an active pilot, held a minimum rank of Lt. Colonel. A mission was usually done with 16 aircraft flying as 4 flights of 4 aircraft for each Squadron. The three squadrons that made up the 56th were the 61st, 62nd, and 63rd Fighter Squadrons. This is larger than their British counterparts whose Squadrons usually comprised of 15 aircraft (12 flying in 3 flights of 4). The British used a similar formation of 3 Squadrons called a Wing. The British first flew in wing formations towards the end of the Battle of Britain, in an attempt to get a more concentrated fighter force to intercept the vastly superior numbers of German Bombers. Prior to that interceptions were either Squadron Scrambles (from the ground) or Squadron Intercepts from their individual patrol zones. Note that a squadron intercept could result in a single flight of 4 aircraft being vectored to attack mixed formations of 100+ bandits (bombers and fighters). This was because the British forces were spread so thin that a single squadron had to patrol vast areas, necessitating each squadron to split into individual 4 aircraft flights. The wing tactic when implemented proved so successful that when the US entered the European theatre they adopted it from the beginning.

The 56th FG was known as "Zemke's Wolfpack." Most Fighter Group Commanders were young and under thirty years old. They carried immense responsibility. Not only were they the combat leader of the fighter group, they also commanded the Service Group, indeed they commanded the entire airbase. In the U.S. Air force today these same functions are commanded by a Brigadier General. Col. Zemke, CO of the 56th Fighter. Group. was 28, his successor at the 56th was Col. Schilling, 26 years old. Squadron commanders were about 24 years old on average. Flight commanders and other flying officers were as young as twenty .

With the coming of May, escort operations begin. The 78th claims one German fighter and two probables while escorting heavy bombers to Antwerp. In exchange, three of the 78th's P-47's fail to make it home. The 56th is doing even worse. After 31 combat missions, they have yet to claim a single enemy fighter against their several losses. Eventually, they score their first victory during a sweep over Rouen on June 12th. On the very next day, Robert Johnson got his first kill, blasting an Fw-190 to pieces. However, on the 26th, the 56th lost five Thunderbolts with four more shot to pieces. All they can claim is two German fighters.

Several P-47D-2-RE fighters on a British airfield, circa July 1943. Not uncommon at the time, many P-47's operated off of unpaved sod fields.

It

was on this mission that Johnson's P-47 is crippled by enemy fire. Refusing to

break formation (after being chewed out for doing just that when he gained his

first victory) Johnson repeatedly tried to warn his Group of attacking Fw 190's.

For some reason, no one heard his frantic radio calls. Johnson's fighter was

clobbered by German 20mm cannon shells. The engine was hit, the hydraulic system

shot out, spraying Johnson with fluid. His canopy was jammed closed and his

oxygen system destroyed. The leaking hydraulic fluid and oxygen came in contact

with each other and burst into flame inside the cockpit. Fortunately, it was

only a flash fire, but Johnson was properly singed, losing his eyebrows and

taking on the appearance of a cooked lobster. Having flown without his goggles

(they were being repaired), the mist of hydraulic fluid nearly blinded him and

caused swelling that threatened to eliminate what limited vision he retained.

Without oxygen, hypoxia began to cloud Johnson's reasoning. In a panic, he

fought to get out of the wrecked P-47. The canopy would not slide back more than

a few inches. Jamming his feet against the shot up instrument panel, he pulled

with all his considerable strength. No luck, it would not budge. One of the side

plexiglass panels had been blown out of the canopy. Johnson tried to squeeze

through it, but his parachute snagged. No sense in climbing out unless he brings

his chute with him. What to do?

This well known photo shows the bottom portion of Johnson's rudder having been blasted away by 20 mm cannon shells.

While

Johnson was struggling with his situation, the P-47 was rapidly descending. As

he lost altitude, the effects of hypoxia were wearing off and the cobwebs began

to dissipate. Quite suddenly, it dawned on him that the Thunderbolt was actually

flying. Upon this realization, Johnson decided to see how far he could nurse it

towards the English channel. He eased off the throttle and the Pratt &

Whitney radial stopped its shaking. The big fighter answered its controls with

authority. Johnson was elated. Maybe, just maybe, he could make it home.

Then he saw it. Sliding in from his left rear, a fighter closes in. But,

whose fighter? Then, he recognized it. A beautiful but deadly Fw-190 with a

gleaming yellow nose. Flying just off Johnson's wing, the German pilot scans the

shot up P-47. Wondering what is going through the German pilot's mind, Johnson

watches as he eases away and swings around in a graceful turn; sliding in behind

the Thunderbolt. Knowing full well what's to come, Johnson grabs the seat

adjuster lever and drops the seat full down where he is afforded the full

protection of the armor plate behind the seat. Johnson thinks to himself;

"let him shoot, this Thunderbolt can't be hurt anymore than it already

is." The Fw 190 opens up on the flying wreck. Like hail on a tin roof, 7.92

mm rounds pour into the Jug. What, no 20 mm? Thankfully, these have all been

expended in some other fight. Johnson sits, hunkered down behind the armor as

the German pilot ripsaws the battered Thunderbolt with hundreds of rounds.

Finally, his anger building, Johnson decides that he must do something.

Kicking hard right and left rudder, the big fighter yaws right, then left. This

scrubs off speed and caught off guard, the German cannot avoid over-running the

P-47. Johnson sees him go by, but is unable to see anything through his oil

covered windscreen. Shoving his head out through the shattered canopy, Johnson

sees the Fw 190 turn gently to the right. Seeing an opportunity, he kicks hard

right rudder, skidding the Thunderbolt, Johnson depresses the gun switch button.

A stream of tracers heads towards the German fighter. But, it doesn't falter.

Instead, it continues around in a perfect turn and slides in alongside the

perforated P-47 once again. Johnson makes eye contact with the German pilot. He

can see the dismay on the German's face. There is no way that this American

fighter can still be flying. It is impossible that it could absorb such a

pounding and keep on flying. The Focke Wulf eases out to the right, and slides

back into perfect firing position once again. Johnson cowers behind his armor

plate as 7.92 mm bullets rain upon the utterly mangled Thunderbolt. Just when

Johnson is convinced that it will never stop, he stamps down hard on the rudder

pedals again. This time the German expects just such a move and pulls off his

throttle. The dappled 190 eases up on Johnson's wing once again, the German

pilot shaking his head in silent amazement. They fly this way for several

minutes. Finally, the German waves an informal salute and slides in behind

Johnson's invulnerable fighter for the third time. As before, the Jug is pounded

by streams of lead. The Fw 190 swings gently from left to right, spraying the

indestructible P-47 with an incessant barrage of machine gun fire. Suddenly, it

stops. The Focke Wulf eases alongside again. The German looks over the

Thunderbolt. The pilot stares with a look of admiration on his face. Pulling

even with Johnson, the 190 wags its wings in salute and peels away in a climbing

turn. Having fired his last rounds at the stubborn Jug, the German heads for

home, certainly convinced that the mauled fighter will never make home.

Another well known photo showing the damage to Johnson's canopy that caused it to jam. The large holes are from 20 mm cannon hits. The smaller holes are mostly from 7.92 mm bullets.

Finally

free of the FockeWulf, Johnson suddenly realizes that during the entire attack,

he had depressed his mike button. Releasing the button, the accented voice of an

Englishman fills his headphones. "Hello, hello, climb if you can, you're

getting very faint". It was Air-Sea Rescue. They had heard the entire

fight, including Johnson cursing his tormentor. Johnson's spirit soars, and he

responds, "I'll try, but I'm down to less than 1,000 feet". Shouting

with joy, he eases back on the stick. Not only will the Thunderbolt fly, hot

damn, She'll climb! Slowly, Johnson nurses the P-47 up to 8,000 feet. The big

fighter hauls herself up, instilling greater confidence in a man who was ready

to bail out but a few minutes before. "Blue four, blue four, I have you

loud and clear. Steer three-four–five degrees."

"I can't do that mayday control, my compass is shot out" answers

Johnson.

The calm British voice issues instructions to "turn slightly

right", and continues to provide course corrections until, after 40 minutes

Johnson spots the coast of Dover through broken clouds. Directed to an emergency

airfield, Johnson circles but cannot spot the sod runway. After checking his

fuel, he pushes the mike button;

"Mayday control, this is blue four, I'm ok now. I'm going to fly onto

Manston. I'd like to land back at my outfit."

Johnson continues on to Manston. Contacting the tower, he describes his

situation. The last test comes as he moves the landing gear lever to the

"down" position. Not only does the gear drop and lock, but by some

miracle, the tires have not been hit. Easing onto the grass, Johnson has no

flaps and no brakes. The big fighter does not slow and is heading towards a row

of RAF Spitfires and Typhoons parked at the end of the runway. In desperation,

he stomps on the left rudder pedal. The Thunderbolt ground loops and slides

backwards in between two of the British fighters just like it had been parked

there. Robert

Johnson and his crew chief, Pappy Gould, pose in front his new P-47D-5-RE. This

fighter was the replacement for his battered and scrapped P-47C. Johnson would

name the new fighter "Lucky". Slowly, Johnson gathers his wits and removing his parachute, squeezes out of

the shattered canopy. Once on the ground he realizes the extent of the damage.

Not only to the plane, but to himself. A bullet had nicked his nose. His hands

were bleeding from the shrapnel of 20 mm shells that exploded in the cockpit.

Two 7.92 mm rounds had hit him in his leg. 21 holes from 20 mm shells are

counted in the airframe. He quits counting bullet holes when he reaches 100. It

seems as if every square foot of the fighter has a hole in it. Somehow, the P-47

had shrugged off the damage and refused to die. Johnson will recover quickly.

The Thunderbolt will not. It was scrapped on the spot, very little could be

salvaged that was not damaged.

Robert Johnson would go on to shoot down 28 (revised down to 27 after the

war) German fighters, with 6 probables and 4 more damaged. After the war,

Luftwaffe records indicated that Johnson might have shot down as many as 32

German fighters. Johnson flew 91 combat missions. On those missions, he

encountered German fighters 43 times. In 36 of the 43 encounters, Johnson fired

his guns at the enemy. A result of those 36 instances where he fired on German

aircraft, 37 of those aircraft were hit; with as few as 27 or as many as 32

going down. Rather impressive for a pilot who flunked gunnery school.

Boleslaw

"Mike" Gladych and his enemy with code

"13".

Written

by Dariusz

Tyminski

.

In the photo above are Polish fighters from the 61st Squadron, 56th Fighter Group. From left side: Boleslaw Gladych, Tadeusz Sawicz, Francis Gabreski, Kazimierz Rutkowski, Tadeusz Andersz and Witold Lanowski.

Boleslaw

Gladych was born on 17 May 1918 in Warsaw. In the beginning of 1938 he joined

the Officer Pilots' School in Deblin. By September 1939 Gladych had not yet

completed his fighter pilot's training, yet he had begun flying PWS-10, PZL P-7

and PZL P-11 planes as early as May 1939.

Escaping from the Romanian internment camp Turnu Severin he

reached France, where he joined the recently formed volunteer

"Finnish" Squadron, intended to take part in the Finnish-Soviet war.

Except for two French pilots (Maj. Demarnier and Capt. Pougevain) all the

volunteers were Polish. It must be kept in mind that Poland, following the

Soviet aggression of 17 September 1939, practically was at war with Soviet

Russia. Anyway this expedition never was realised and the squadron was changed

to a completely Polish unit named Groupe de Chasse I./145. The appointed

commander was Mjr. Kepinski, with Capt. Wczelik and Mjr. Frey as flight leaders.

The unit was equipped with Caudron Cr-714 "Cyclone" fighters. This was

a new and interesting fighter design, but suffered from many technical troubles.

Nevertheless, these were the aircraft the Polish pilots had to fly against the

Germans, and they fought bravely with them against the Germans after the May

1940 attack.

Participating in "Cyclone" (on 10 June 1940 ?) Gladych

had a dramatic air duel with a Bf 109. After a long and tough combat, the German

managed to hit the Polish fighter severely. But realizing Gladych's hopeless

situation, the pilot of the Messerschmitt - with the call-code "13" -

acted with great honour: he simply waved his wings and disengaged.

After the French surrender, 2/Lt. Gladych arrived in the British

Isles. On 21 April 1941 he finished training on British fighters and was posted

to 303 Squadron. Five days later he downed his first enemy plane achieving the

250th air victory among all During the period 9 July 1942 - 16 September 1942, Gladych was a

member of 302nd squadron "City of Poznan", unit call-code "WX".

Following an operational break, he returned to the same unit on 4 December 1942.

By the beginning of 1943 he In the spring of 1943, during a heated battle near the town of

Lille, France, Gladych downed one enemy fighter. But soon after, an FW 190

scored damaging hits on the "Spitfire". Although severely shot up,

Gladych's aircraft somehow remained flying. The German pilot flew close to him,

waved his wings and disengaged. Gladych noticed the clearly visible number

"13" on the fuselage of the "gentelman's" FW 190!

Misfortune hit Gladych hard in the autumn of 1943. He mistakenly

almost shot down the aircraft carrying British Prime Minister Winston Churchill.

The English High Command demanded Flight Lt. Gladych should be punished, and

decided to "ground" him - very tough punishment for a fighter pilot.

But one day Gladych met Capt. Francis Gabreski (or rather

Franciszek Gabryszewski, in Polish), who previously had been in the Polish

Fighter Squadron. By now he was a very well-known fighter pilot. Gabreski

offered him flights in the U.S. 56th Fighter Group, outfitted with P-47

"Thunderbolts". Soon, Gladych organized battle training for

unexperienced American pilots. With the 61st Fighter Squadron he took part in

many combat flights. On 21 February 1944 he downed 2 Bf 109s on one mission.

Gladych's next run-in with the call-code "13" took

place on 8 March 1944. On this day American bombers flew to Berlin. In combat

with attacking FW 190s, Gladych claimed one. But soon he was left alone with

dwindling supplies of both ammo and fuel in his P-47 HV-M "Pengie II",

facing another two enemy aircraft. The two Germans, one of them with call-code

"13", held their fire and told Gladych to land on the nearby Vechta

airfield. The Polish pilot went down, dropped his landing gear and prepared to

land. When he was over airfield he suddenly opened fire with his remaining

ammunition. Responding intensly, the flak gunners accidently hit the escorting

Focke-Wulfs. Gladych gave full throttle and escaped. When he crossed the coast

of the English Channel his P-47 ran out of fuel, giving him no choice but to During his duty in the 61st Fighter Squadron, 56th Fighter Group

Gladych scored a few more kills, shown in the table below. Some sources say her

achieved eleven with the USAAF.

Boleslaw Gladych had no opportunity to fight in Polish (or

British) units, and he served in the USAAF until the end of the war. His

American friends nick-named him "Mike Killer". Gladych was never

officially included in any American unit, he was only a "guest star"

of the 56th. A few days after the end of the war he was simply kicked out of the

U.S. Armed Forces. Apart from Gladych, a few other Polish pilots flew with

success in 61st FS, 56th FG - Witold Lanowski (1 FW 190 on 22.06.1944, 1 Bf 109

on 27.06.1944, 1 Bf 109 on 6.07.1944 and on 18.11.1944) and Tadeusz Andersz (1

Bf 109 on 9.04.1944).

Epilogue. In 1950 Gladych was in Frankfurt, Germany. He

accidentally encountered a meeting of the "Gemeinschaft der Ehemailigen

Jagdflieger der Luftwaffe". Asked by his wartime adversaries of his war

memories, he told the story about the mysterious fighter with the code

"13". As he ended his story, he noticed one of the attending German

pilots was really touched. It was the pilot of this "13" in all three

cases. His name is Georg Peter Eder, an ace with 78 victories who was himself

shot down 17 times!

Boleslaw Gladych belonged to the top-scoring Polish aces -

officially ranked fifth with a record of 14-2-1/2. Currently he is living in the

USA.

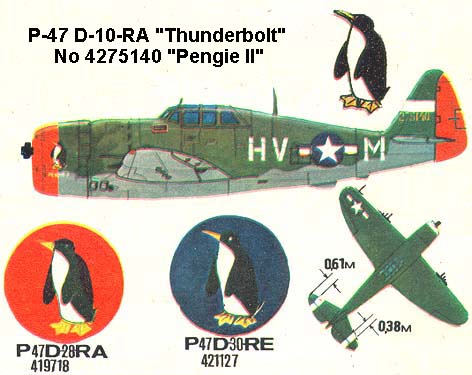

Below is shown the color scheme of one of Gladych's

"Thunderbolts". It is the P-47 D-10-RA No 4275140 "Pengie

II" from 56th FG, 61th FS, 8th AF - and the plane in which Gladych fought

on 8 March 1944. Having run out of fuel it crashed. Also displayed are a few of

Gladych's markings used on other P-47s. "Pengie" is the

nick-name of his girl-frind, a pretty Canadian in the WAAF.

Polish pilots in the UK. On 23 June 1941, the squadron took part in two missions

over France. On both occasions they were involved in combat and claimed 5-4-0

victories in total. Gladych was injured during these missions and his damaged

"Spitfire" Mk V had to crash land on the British coast. In October of

1941 Gladych claimed one confirmed kill.

was promoted to Flight Leader.

bail out. For that mission he was awarded the Silver Star.

Boleslaw Gladych

21.02.1944 2 Bf-109

Boleslaw Gladych

08.03.1944 1 Fw-190

rendez-vous with "13"!

Boleslaw Gladych

27.03.1944 1 Bf-109

Boleslaw Gladych

06.06.1944 1 Bf-109

Boleslaw Gladych

07.06.1944 1 Bf-109

Boleslaw Gladych

05.07.1944 1 Bf-109

Boleslaw Gladych

12.08.1944 1 Ju-88

Boleslaw Gladych

21.09.1944 2 Fw-190

TOTAL:

10 victories